Equines, prairie and carbon storage

Recent advances in the identification of herds have shown a considerable growth in the number of equines (horses, donkeys and hybrids) in France. As of the end of 2008, there were 900,000 equines counted (ECUS 2010).

Even if they remain few in comparison to bovines (19.199 million head identified in 2010, Institut de l’Elevage (Breeding Institute), equines are playing a growing role in the upkeep and restoration of pastures. They are also used more and more to preserve biological diversity in areas with high ecological value (in particular natural reserves) on which they graze, either alone or in combination with ruminants.

© E. Rousseaux – Trait Poitevin / Vaches Parthenaises

At the national level, the horse sector takes part in the upkeep of almost a million hectares of natural prairie.

According to a recent FAO report (Review of Evidence on Drylands Pastoral Systems and Climate Change) published in December 2009, the pastures and runs used for the breeding of herbivores account for carbon sinks which, if they are well managed, can be more important than those of forests. These stocks are fragile, however. In fact, if a pasture is degraded, eroded or ploughed, it emits CO2.

Maintaining such surfaces thus represents a challenge for the stability and protection of climate.

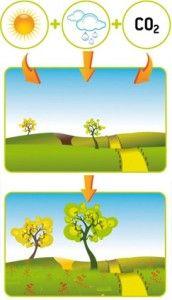

Carbon is essential to life. It circulates in different forms in nature. Present as Co2 in the atmosphere, it is captured by plants which use it to make carbohydrates during photosynthesis. It is then consumed, either by animals or people, or becomes part of the soil as humus, plant residue, etc. At the same time, carbon is also emitted through the breathing of plants and animals, or when organic matter decomposes in the presence of oxygen.

When an ecosystem captures more carbon than it emits, it is called a carbon sink.

© Collection SFET – Pottok

Permanent prairies are, like forests, the earth’s main carbon sinks. INRA research shows that one hectare of prairie or forest immobilises 70 tonnes of carbon in the first 30cm of soil depth and can continue to store carbon year after year. These soils are never ploughed and carbon is stored in them as organic matter which, in the absence of oxygen, decomposes very little. Inversely, as soon as a prairie is ploughed to grow something, its soil is aerated and emits one tonne of carbon per hectare per year.

In France, 11 million hectares of permanent prairie, accounting for one fifth of the French territory, are to be conserved.

How do prairies store carbon ?

Source: Les ruminants et le réchauffement climatique (Ruminants and Global Warming), Institut de l’Elevage, collection Essentielle, 2008

Sources : Institut de l’élevage, FAO, INRA, IFCE, CIV